Block Architecture

Being a UTXO-based blockchain, Fuel is designed with a number of similarities to existing UTXO-based chains, such as Bitcoin. Consult the Bitcoin developer reference for an overview of the minimal block layout required for such a chain.

|

|---|

| Overview of block contents. |

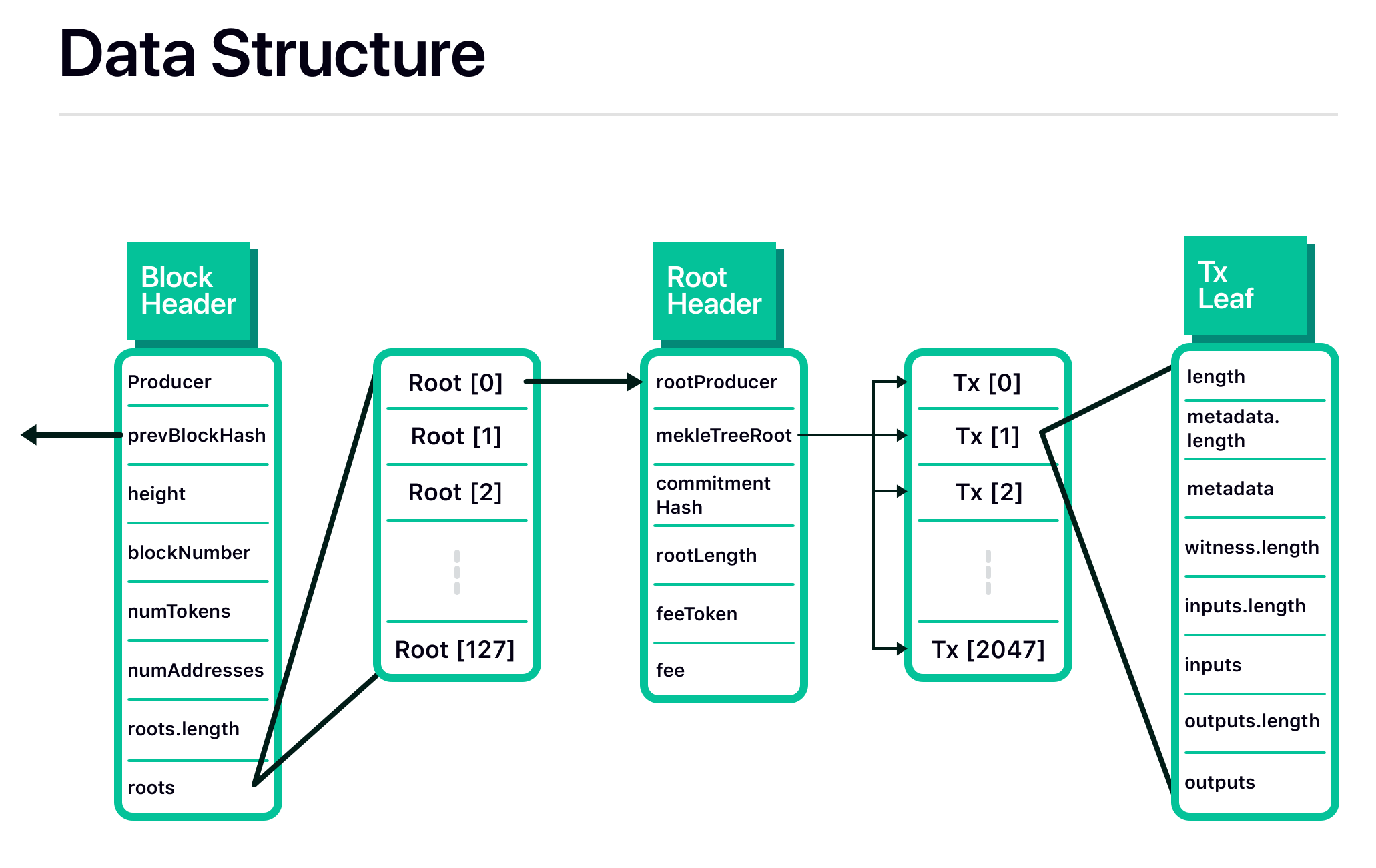

This page describes intuitions behind the top-level data structures, from blocks to leaves in the transaction tree. Discussion on the transaction architecture is relegated to the next page.

Block Header

In any blockchain, block headers commit to a list of transactions, and contain other important metadata. Blocks are block headers plus the explicit list of transactions, but do not exist as an independent data structure in Fuel.

Each block header in Fuel contains the usual suspects: an identifier for the block producer, the previous block header's hash, and the block height (the index of this rollup block in the rollup chain). A few other fields, that diverge from traditional blockchains, are also present.

First, the block number, i.e. the Ethereum block number when this rollup block was submitted to Ethereum, is included. Note that the expressions [block] height and [block] number are used to refer to the rollup block height and the Ethereum block number, respectively.

Note: Including the block number in the header (or, more specifically, requiring an Ethereum block number and Ethereum block hash to match when committing a new rollup block) prevents miners from re-organizing Ethereum and moving a submission transaction to an earlier block number, which could invalidate the timelock conditions of Fuel transactions.

Additionally, the maximum token ID and address ID used through the rollup block (i.e. in this and all previous rollup blocks) is included in the header. The transaction architecture page will discuss these in more details, but for now it is sufficient to know that addresses (token are identified by an address as well) can be registered, which allows them be to referenced by a short numerical ID rather than a full 20-byte address, resulting in smaller (and thus cheaper) transactions.

Note: An attacker can craft a rollup block that includes a transaction with a not-yet-registered ID (i.e. an invalid block). When they see a transaction that proves that block is invalid, they can front-run it with a transaction that registers the ID. Checking for maximum IDs as a block is submitted prevents this griefing vector.

Finally, rather than a single Merkle root of a list of transactions, a list of root header hashes is included. Each root header commits to a list of transactions (in other words, the block header still commits to a list of transactions, though indirectly), and is discussed in the next section.

Fields that are usually seen in layer-1 Proof-of-Work chains, such as a timestamp and a nonce, are omitted. The former is implicit in the form of the Ethereum block number, and the latter is unnecessary since work is not used in the rollup.

Root Header

Each root header commits to a list of transactions directly in two forms, and contains additional metadata that will be discussed shortly. Roots are root headers plus the explicit list of transactions, but do not exist as an independent data structure.

A list of transactions is committed to as both a Merkle root and a simple hash. The simple hash is checked when a new root is submitted on-chain, but not the Merkle root. This avoids the need to Merkleize transactions all the time, and saves on gas costs. If the Merkle root is incorrect, this can be proven with a fraud proof (which uses the simple hash to authenticate the data that will be Merkleized).

Note: Separating block submission into two steps—first submitting one or more roots, then submitting the block header that includes those roots—reduces the costs of a race condition where multiple block producers submit a block at the same time and only one is valid (and the other transactions would fail and cost gas). By making block submission extremely gas-cheap, this race condition is no a longer costly mistake. There is no race condition on submitting roots.

Note: The size bound on the list of transactions is chosen such that Merkleizing any individual list of transactions can be done within the gas limit of a single Ethereum block (with a large margin of safety).

Two transaction fields are hoisted into the root header: the fee token ID and the feerate. By enforcing that all transactions under a single root pay fees in the same token at the same rate, we can avoid needing to repeat these values for every transaction, and instead only specify them once in the root header.

Note: Transactions still sign over the fee token ID and feerate values, to avoid malicious root submissions. The values are implicitly part of the transaction data that is signed. See the next section for implicit vs explicit transaction data.

Transaction Leaves

The transaction architecture can be found in the next page. It is recommended to read it first, before returning to complete this section.

Each transaction leaf (i.e. leaf in the Merkle tree of transactions that are committed to in a root header) contains all the required data to reconstruct the state transition defined by the transaction unambiguously.

- A list of witnesses, which authorize spending a state element in this transaction.

- A list of inputs and metadata (one metadata per input). Each input provides enough information to "unlock" the state element being spent, but does not explicitly identify the state element by ID.

- A list of outputs, which each describe the spending conditions for a new state element.

Metadata is inserted by the root submitter as a means of uniquely identifying the state element being spent at each input. For regular UTXOs this would be the block height, root index, transaction index, then output index. This replaces the traditional UTXO ID (usually: a hash of the transaction and output index) with a much more compact representation.

Note: Metadata is malleable by the root submitter, and is thus not signed over by the transaction sender.